January 20, 1943

As everyone welcomes 2020, many often remember the past to see how far life has evolved. Thus, for the first article of the New Year, I thought it best to discuss the history of the brave men that served in the 90th Bombardment Group during World War II. The bombardiers of “The Best Damned Heavy Bomb Group in the World” remind us of the price some pay so that others may examine the past to create a better future.

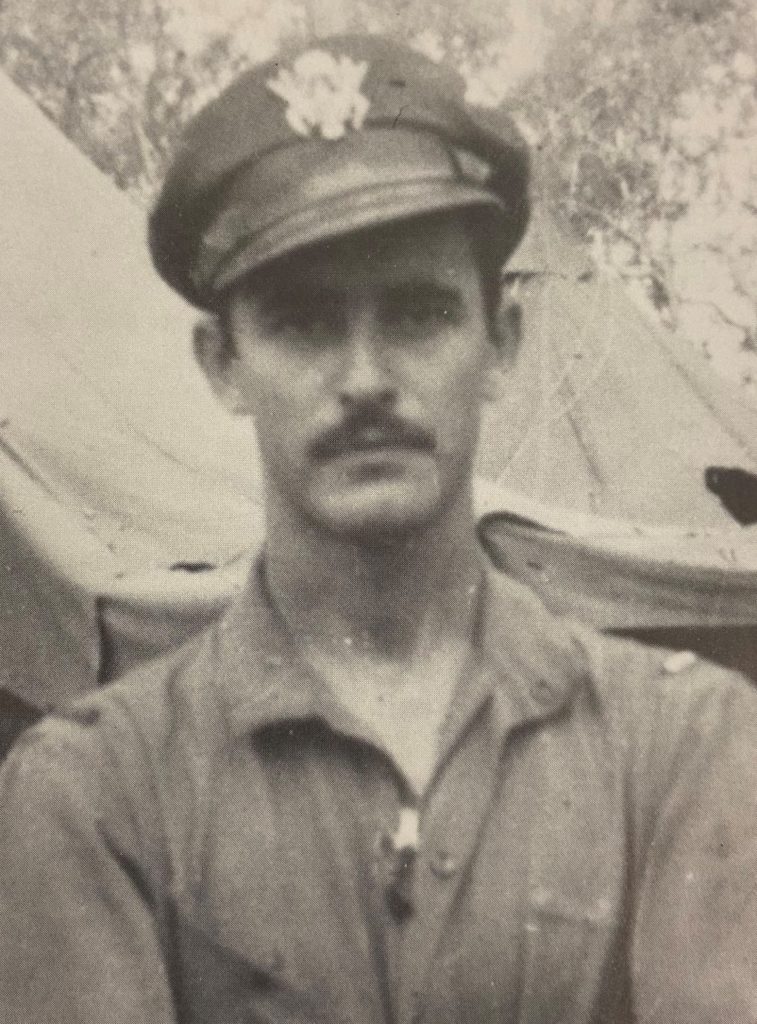

On January 20, 1943, First Lieutenant James A. McMurria and the crew of the Waltzing Matilda (B-24 Liberator) conducted a reconnaissance mission over the north coast of Papua New Guinea. As McMurria reduced the plane’s altitude to get a better view of Wewak harbor, the men from the 321st Bombardment Squadron spotted twenty-seven Japanese Zeros, two naval transports, and three destroyers. After reporting the intelligence, all radio signals from the Waltzing Matilda ceased. Many assumed the worst—that the Japanese shot down the B-24 after its crew discovered their location. Nevertheless, personnel from the 319th, 321st, and 400th Bombardment Squadrons conducted multiple search and rescue missions. While the volunteers downed over twelve enemy fighter aircraft during their searches, none of the crews located the missing Liberator.

Unknown to the rest of the 90th Bombardment Group, McMurria and eight other crew members survived a one hour dog fight against twenty-seven Japanese Zeros before the Waltzing Matilda crashed into the water near Wewak. After floating ashore, the stranded Airmen sought refuge with a group of natives. For more than a month, the crew traversed the outlying islands in their endeavor to make it to mainland Papua New Guinea. Ultimately, a group of Japanese soldiers captured the men shortly after they landed ashore the Sepik River.

Lt. McMurria’s account of the affair provides vivid details about the life of a Japanese Prisoner of War during World War II. Once the Japanese soldiers captured the men, “they were hung on bamboo poles . . . and hauled back to the . . . canoe. . . . Taken to Wewak, the fliers were interned in a well-like hole, where food and water was periodically lowered to them in a bucket.” After being tortured for ten days in Wewak, the soldiers transported the airmen to the Tunnel Hill Prison Camp in Rabaul, where the Waltzing Matilda crew joined seventy other American and Australian prisoners. In Rabaul, POWs “were placed in . . . 10 x 14 foot downtown cell[s]” with thirteen other men. The Japanese subjected the prisoners to a variety of torments, ranging from “water treatment” to “human guinea pigs.” Of the seventy prisoners present at the Tunnel Hill Prison Camp in June 1943 when McMurria and his crew arrived, only six survived their time as Prisoners of War.

After losing forty-three percent of his body weight and experiencing the cruelest atrocities imaginable, the Japanese released the ninety-three pound Lieutenant in September 1945. Despite being surrounded by constant death, he remained resilient throughout his imprisonment. As he watched American B-24 Liberators, A-20 Havocs, and P-38 Lightnings fly over Rabaul, he constantly reminded the prison guards that his countrymen were coming to not only save him, but to also end the war. Undoubtedly, his story provides a glimpse into the history of the 90th Bombardment Group, World War II and the legacy that the Airmen at the 90th Missile Wing continue to uphold today.

(This story is a result of Lt. McMurria’s first-hand account of his time at the Tunnel Hill Prison Camp, as well as research conducted by John S. Alcorn, which is thoroughly detailed in his book The Jolly Rogers: History of the 90th Bomb Group During World War II.)